REJECTING THE OLD AND CREATING THE NEW

By Anshul Sajip

Undoubtedly, the horrors of Hitler's brutal and inhumane dictatorship are something that has scarred history. But what if I told you that it indirectly led to a remarkable wave of innovation in philosophy, literature and cinema, unparalleled in recent times, which has profoundly affected Western thought?

The devastated France of the 1940s and 1950s was especially at the fore of society's difficult confrontation with modernity - a confrontation that destroyed the values of the old Enlightenment system and its ways of thinking. Indeed, the foundations of this radical unfolding movement were being laid at the very heart of French culture.

The liberation of Paris

Post-modern thought emerged to challenge the Enlightenment assumptions of rationality, reason and progress, in a new and irrational world where philosophers such as Barthes, Foucault and Derrida were stunned to confront the rise of fascism, the atomic bomb and numerous genocides. The concentration camps of the Holocaust were organised by modern bureaucratic systems, and the atomic bomb was considered a triumph of modern science, both of which the Enlightenment had fostered and had assumed would be beneficial to humanity. However, the shock that things turned out so differently undermined people's faith in old values, so instead they turned to questioning how the world was seemingly regressing rather than moving towards reason and justice. The great thinkers of the time deemed the modern world to be a failure.

Foucault, for example, critiqued the treatment of the mentally ill during the Enlightenment, as they were reviled, rejected and even incarcerated as their insanity was not compatible with the notion of Reason that was at the heart of the Enlightenment project - he called this time period 'The Great Confinement'. The atrocities experienced during World War II further skewed ideas of knowledge and certainty, leading to arguments that an objective reality does not exist. New theories were flourishing, both questioning former methods but also proposing ways of moving forward into a rapidly modernising France.

Similarly, literature echoed the sense of confusion and disorientation that many experienced during and after French Occupation; instead of seeking to reflect reality, novels pursued the uncertainty and precariousness of existence. Alain Robbe-Grillet's novel La Jalousie explores a husband's feelings of obsessive jealousy and fear that his wife is being unfaithful. It is never revealed whether she is or not. In such way, authors aimed to capture the conflicting emotions and turmoil that characters were experiencing and project this onto the audience, something not done in the works of the 19th century.

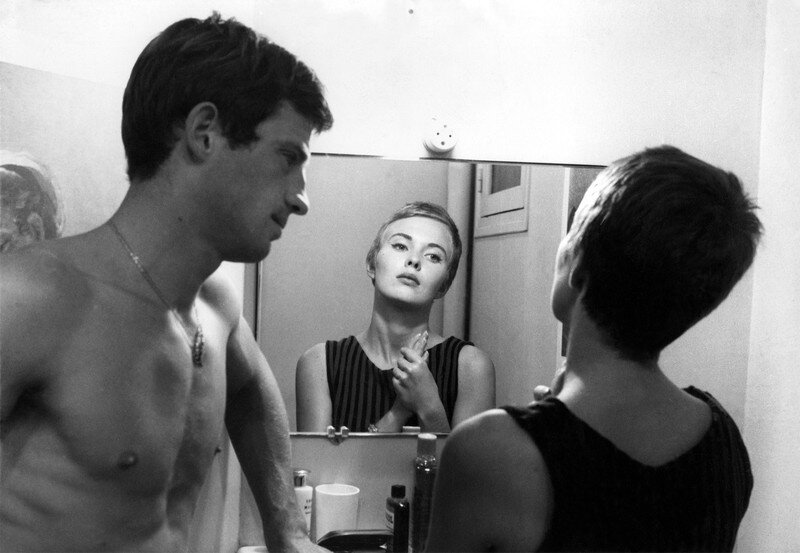

À Bout de Soufflé (Jean Luc Godard, 1960)

Finally, nouvelle vague cinema appeared alongside new philosophy and the new novel. This was a revolutionary rejection of the Hollywood style of film-making, which was studio dominated and resulted in stock formula films. Directors such as Truffaut and Godard wanted freer shooting and more space for actors to develop, helping to convey the complexities and uncertainties of life. Their films did this and so used visual imagery to criticise the modern world by exposing its sexual, moral and economic corruption, with many films ending unresolved in order to engage the imagination and introspection of the audience.

Truffaut's film Jules et Jim in 1961, about two men who love the same woman, epitomises the nouvelle vague movement, making it to number 46 on the Empire Magazine's "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema". Being both popular and accessible, stylish but without a real plot, its main focuses are on emotion rather than development, the uncertainty of youth and the power of desire. Indisputably, in the 1950s and early 1960s, the inspiration and ideas for cinema stemmed from this revolutionary French movement, embracing new styles and techniques to question society.

Overall, it is fair to say that the cultural explosion, produced by the shock of the Second World War, was a definite attempt to reject the values of the Enlightenment and pre-war ideas and possibly enabled France to become the cultural centre of Europe and perhaps even the whole world, just as it had been during the 18th and 19th centuries.