THE ANTARCTIC EXPLORER - ROBERT FALCON SCOTT

By Senan Karunadhara

“But take comfort in that I die at peace with the world and myself – not afraid.” – Robert Scott. A quote taken from Scott’s last letter to his Mother, Wife, and Son before he passed away in Antarctica.

It is always important to remember the unspoken, yet important, contributors to history and the knowledge of the wider world that we have today, especially the scientific and geographical one. Exploration of unknown places and unproven theories was and will continue to be, a cornerstone in the development of mankind’s ability to understand its world. Whether it be the great Christopher Columbus and the discovery of the Americas or Captain Cook and the discovery of New Zealand and the Australian east coast, we owe our present knowledge of the world to the explorers of the past. However, what of the unsuccessful explorers, those who gave their lives to further our understanding of the world yet ended up dying as a result of their desire. Enter, Captain Robert Scott and the campaigns to the Antarctic.

“I may not have proved a great explorer, but we have done the greatest march ever made and come very near to great success.”

Robert Scott, or ‘Scott of the Antarctic’ joined the Royal Navy as a Cadet at just age 13. His brilliance on the battleships and commitment to his crew earned him the attention of one of the greatest living Antarctic explorers, Sir Clements Markham, the secretary of the Royal Geographical Society. After a vigorous interviewing process, the Society appointed Scott to command the National Antarctic Expedition between 1901-04 on the HMS Discovery. This was the first official British exploration of the Antarctic in 60 years. The expedition is famed for its numerous discoveries, these included the discovery of the only snow-free Antarctic valley, the Cape Crozier Emperor Penguin colony and even more. 1903 was very significant for Scott in particular, it was the second year and journey of the expedition; the crew was tasked with scaling the western mountains of the interior of Victoria Land. This is where Scott took his first major risk, instead of simply ascending the mountain and then returning as the party of the previous year did, Scott decided to march his men west, this took an additional 8 days of walking over unknown, featureless land; supplies were running extremely low and all the crew had to rely on was Scott’s navigation abilities. Scott nearly encountered death during this march when he nearly fell down a crevasse, this occurred just before he discovered Antarctica’s only snow-free valley. Historian David Crane asserts that this was ‘one of the great journeys of polar history.’ When Scott returned to England in 1904, he was promoted to captain.

“We are showing that Englishmen can still die with a bold spirit, fighting it out to the end.”

June 1910, Robert Scott sets out on his second exploration of the Antarctic – its aim was relatively simple, to study the Ross Sea and reach the South Pole. The crew of 12 was well equipped with horses, dogs and other equipment that could have proved to be extremely useful, however, in late 1911, the weather conditions were too harsh for the equipment to function and for the horses and dogs to provide any service, as a result, they were sent back. On December 10th the 12 men began to climb Beardmore Glacier but 21 days later 7 of them were sent back. By January 17th the 5 remaining men had finally made it to the pole – they had finally discovered the South Pole. Only, they hadn’t, though they did reach the pole, they hadn’t discovered it, upon arriving they were greeted by the unpleasant sight of the Norwegian Flag – Roald Amundsen had discovered the pole only a month before.

The men had to begin their 1500km descent immediately. The weather conditions proved to be fatal for all of the explorers. One died in mid-February. In March, another was suffering was frostbite and believed that he was holding back his group, as a result, he walked out into the freezing conditions. The rest, including Scott, died of starvation and exposure in late March – they died only 20km away from a supply stop.

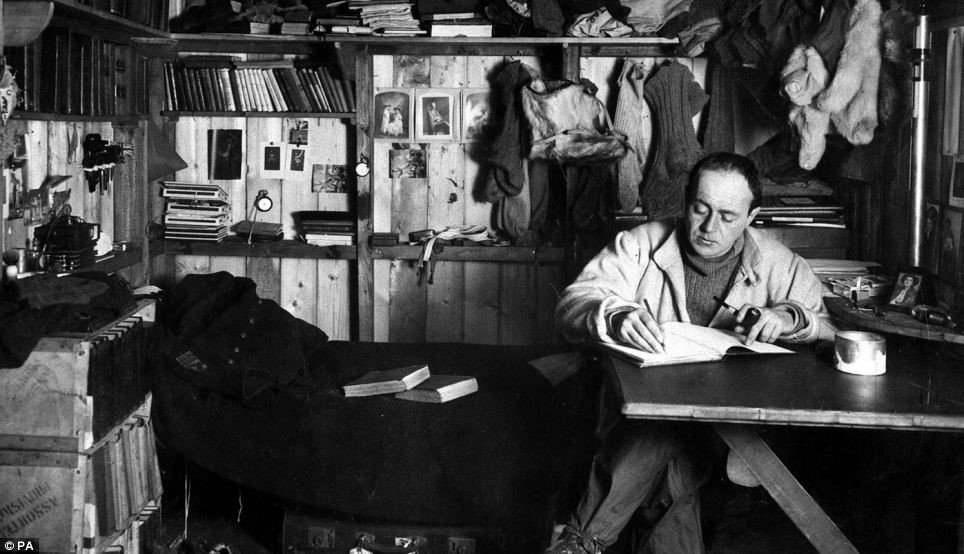

Many months later bodies were discovered, as were Scott’s letter to his family and diary entries. The bodies were buried under the tent with their graves being marked with an ice structure. England remembered him fondly after hearing about Scott’s death, he was considered a hero of courage and patriotism – Scott’s widow was given a Knighthood that would have been given to him. However, in the 1960s the reputation of Scott was soiled by polar historian Huntford who wrote numerous books attacking Scott’s reputation referring to him as a blundering idiot – this image of Scott lasted a considerable amount of time.

So, what is so important about Robert Scott, who to put it bluntly, was a failure in history. Well, Robert Scott was not remembered for his successes and failures in his missions but was instead loved for his commitment to the development of human understanding. He was proof to every British citizen that participation, passion and dedication were just as important, if not more so than success.

“Each man in his way is a treasure.”